Dayton and the "Burnt District"

After a number of defeats in the lower Valley, Confederate General Jubal Early was forced to retreat south and seek refuge in the Blue Ridge Mountains east of Harrisonburg. His Union adversary, General Philip Sheridan, pursued him all the way to Brown’s Gap east of Port Republic. With Early’s forces isolated in the mountain pass, Sheridan established headquarters in Harrisonburg and began to initiate General Grant’s orders to destroy the agricultural abundance of the Shenandoah Valley. From the cover of the Blue Ridge, the Confederates watched for days as Union troops set fire to countless barns, mills, and corncribs.

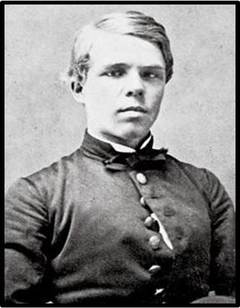

Union Lt. John Rodgers Meigs

Union Lt. John Rodgers Meigs

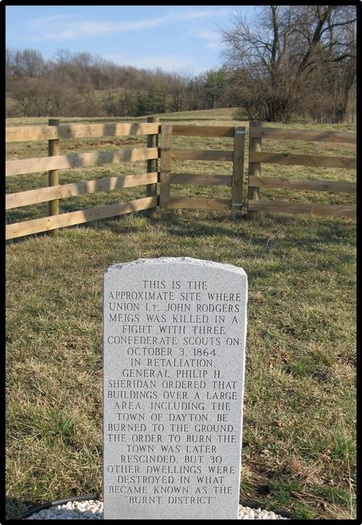

On October 3rd, a small group of Confederate cavalry scouts ventured west in order to assess the strength of the Union forces. A light rain fell as Frank Shaver, George Martin, and F.M. Campbell rode across the Valley Pike and into the hills that overlooked the town of Dayton. Dusk was nearing and the three riders were about to turn back when they unexpectedly came across a Union officer and two orderlies. Lt. John Rodgers Meigs called out for them to halt, but the Confederates kept riding away in the hopes of avoiding a confrontation. As Meigs galloped toward them, Campbell asked Shaver, “Shall we run or fight?” Shaver slowly drew his concealed revolver and prepared to make a stand. When the Union Lieutenant caught up to them, Martin revealed his revolver and demanded Meigs’ surrender. Meigs fired his gun and the bullet struck Martin in the inner thigh. Shaver and Campbell quickly returned fire, and Meigs fell from his horse. One of the Union orderlies surrendered while the second escaped into the woods. The Confederates rapidly galloped back to their lines as the Union Lieutenant lay dead in the road.

Meigs Marker - north of Dayton on Meigs Lane

Meigs Marker - north of Dayton on Meigs Lane

The death of John Meigs was a significant loss to Sheridan. In addition to graduating first in his class from West Point, Meigs’ father was the Quartermaster General of the Union Army, Montgomery Meigs. Aside from losing such a talented young officer, Sheridan was also disgraced by allowing the son of a superior officer to be killed under his watch. His anger only deepened when the surviving orderly mistakenly reported that Meigs had been ambushed by local civilians. Sheridan later wrote, “Lieutenant John R. Meigs, my engineer officer, was murdered beyond Harrisonburg, near Dayton…Since I came into the Valley from Harper’s Ferry, every train, every small party, and every straggler, has been bushwhacked by the people.” The supposed murder of such a valued officer compelled Sheridan to retaliate. Within hours of Meigs’ death, orders came down that the town of Dayton and all houses within a three-mile radius of the murder scene were to be burned.

The following morning of October 5th, Union soldiers went from door to door and informed residents of the coming destruction. The frightened townspeople gathered up their belongings and hastily began stacking them in nearby fields. The tragic scene was compounded by the fact that most residents were peace-loving Mennonites and Brethren who strictly adhered to a doctrine of non-violence. One soldier remembered, “such mourning, such lamentations, such crying and pleading for mercy. I never saw nor never want to see again, some were wild, crazy, mad, some Cry for help while others…throw their arms around yankee soldiers necks and implore mercy.”

The burning parties initiated their devastating work near the site of Meigs’ death, north of Dayton along the Warm Springs Turnpike (present-day Route 42). The townspeople watched in fear as fires spread across the landscape. This devastation took longer than expected, and Dayton gained a day-long reprieve. The scored region ran north of Dayton all the way to Garbers Church Road and the Rawley Pike (present-day Route 33). For years afterward, maps of Rockingham County identified this area of destruction as the "Burnt District."

Lt. Col. Thomas R. Wildes - 116th Ohio Regiment

Lt. Col. Thomas R. Wildes - 116th Ohio Regiment

Despite the desire to avenge Meigs, most Union soldiers were not eager to set fire to civilian homes. This dilemma weighed especially heavily on the conscience of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas F. Wildes of Ohio. After considering the potential consequences, Wildes bravely decided to send a message to General Sheridan that “urged and begged [him] to revoke the order in so far as Dayton was concerned.” When confronted with Wildes’ appeal, “Sheridan read the note and swore, read it again and swore, [and then] examined and cross-examined the messenger.” After a moment of agitated contemplation, Sheridan yielded to the request and rescinded the order to burn the town. Lieutenant Colonel Wildes called his men together and informed them of the change in orders. One of them recalled, “there was louder cheering than there ever was when we made a bayonet charge.”

Years later, the town erected a monument at the corner of Mill and Main Streets with the following inscription: “In memory of Lt. Col. Thomas R. Wildes – 116th Ohio Regiment. Who, when ordered by Gen. Sheridan to burn the town of Dayton, VA in retaliation for the death of a Union officer, refused to obey that order, risking court-martial and disgrace. His refusal and plea to Gen. Sheridan resulted in a countermand to the order, and saved this town from total destruction.” This is one of the only memorials in the former Confederacy that honors the memory of a Union soldier. During the recent sesquicentennial remembrance of the Burning, Dayton’s Mayor named October 6th as “Thomas F. Wildes Day.”

Years later, the town erected a monument at the corner of Mill and Main Streets with the following inscription: “In memory of Lt. Col. Thomas R. Wildes – 116th Ohio Regiment. Who, when ordered by Gen. Sheridan to burn the town of Dayton, VA in retaliation for the death of a Union officer, refused to obey that order, risking court-martial and disgrace. His refusal and plea to Gen. Sheridan resulted in a countermand to the order, and saved this town from total destruction.” This is one of the only memorials in the former Confederacy that honors the memory of a Union soldier. During the recent sesquicentennial remembrance of the Burning, Dayton’s Mayor named October 6th as “Thomas F. Wildes Day.”

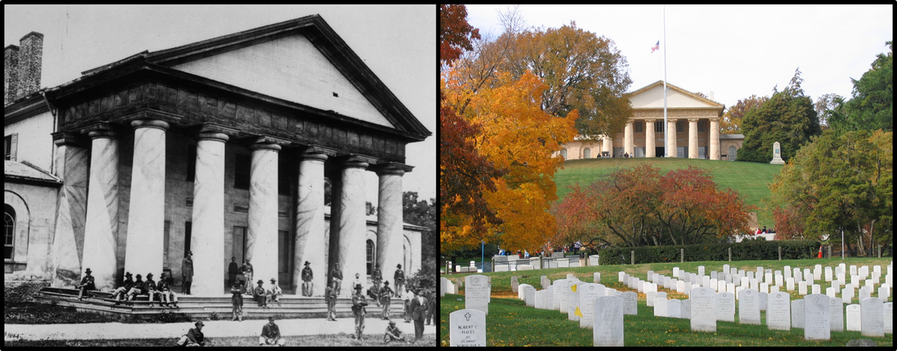

Despite subsequent evidence to the contrary, General Montgomery Meigs maintained that his son had been ambushed and murdered in cold blood. His thirst for vengeance even influenced the site of his son’s burial. Shortly after the war started in 1861, the Union Army occupied Robert E. Lee’s hilltop estate in Arlington, Virginia. Throughout the war, General Meigs sought to make Arlington House uninhabitable by burying the Union dead in Lee’s front yard. At Meigs' personal request, Union dead were even buried along the perimeter of Mrs. Lee’s rose garden. When John Rodgers Meigs was killed in Dayton, his father had him buried on the Lee estate. His remains now rest behind Lee’s mansion in Plot 1, Row 1, Section 1 of what later became known as Arlington National Cemetery.

SOURCES:

Heatwole, John L. The Burning: Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing, 1998.

1864: The Valley Aflame. Staunton, Virginia: Lot's Wife Publishing, 2005.

Heatwole, John L. The Burning: Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing, 1998.

1864: The Valley Aflame. Staunton, Virginia: Lot's Wife Publishing, 2005.