Zenda: An African-American Community of Hope

Correlation to the Virginia Standards of Learning: VS.8a, USII.3a-c, USII.4c, USII.6b, USII.9a, VUS.7b-e

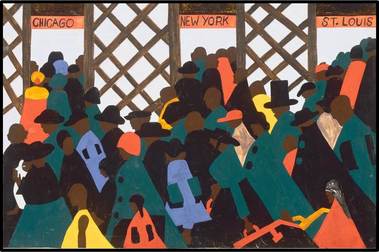

The Migration Series (Panel #1) by Jacob Lawrence

The Migration Series (Panel #1) by Jacob Lawrence

In 1869, William and Hannah Carpenter deeded a significant portion of their farm in northern Rockingham County to the United Brethren in Christ, to be set aside for the “colored people in this community…and to their successors forever.” The land was divided into small lots so that freedmen and formerly enslaved persons could establish free and independent lives in the early days of Reconstruction. Henry Carter, Milton Grant, William Timbers, and Richard Fortune became the first freedmen to settle in a community that later became known as “Zenda.” By the turn of the century, Zenda had grown into a vibrant community with over 80 residents, a post office, schoolhouse, chapel, and a cemetery. However, the village began to dwindle during the early 1900s as industrialization lured rural Americans to growing cities and towns. In addition to better jobs, northern cities also offered African-Americans an escape from the countless oppressions of the Jim Crow South. In the wake of the Great Migration, only one family of color remained in Zenda by 1940.

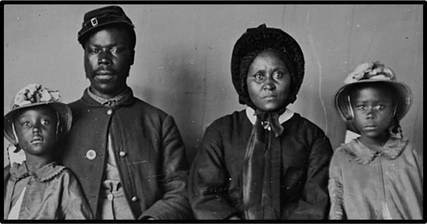

Freedman turned Union soldier with his wife and children

Freedman turned Union soldier with his wife and children

Despite its short existence, Zenda represented a vital step in the long evolution of civil rights. Prior to emancipation, enslaved persons did not possess legal rights and were treated as property. Their marriages did not have legal status, and enslaved parents did not have custody to their own children. This disregard for the slave family was further reinforced by the denial of a surname identity (last name) – the enslaved were referred to by their given names (first names) and were often forced to adopt the surname of their master. Following emancipation, formerly enslaved persons not only took last names of their own choosing, but the new residents of Zenda were now able to sign these names to deeds, and be recognized as land owners. These new citizens also enjoyed the right to legally marry, and they now established families without the fear of having their children sold away from them. Unlike the nameless graves of the plantation, Zenda residents paid respect to the lives of their elders by burying them in marked graves within a local cemetery. In Zenda, the formerly enslaved were empowered by the opportunity to discover their identity as free people.

Rockingham County School Administrators tour Long's Chapel (September 2015)

Rockingham County School Administrators tour Long's Chapel (September 2015)

Not long after the first residents arrived, the United Brethren in Christ made arrangements to build a chapel that would serve as church, meetinghouse, and school for the Zenda community. Jacob Long, a nearby landowner and postmaster, oversaw the construction of a one-room chapel that stood 20 feet by 30 feet with two windows on each side. In addition to volunteering his time and labor, many believe that Mr. Long paid for much of the construction out of his own pocket. This may explain why grateful residents later referred to the new house of worship as “Long’s Chapel.”

Zenda’s chapel soon provided for the educational as well as the religious needs of the community when a primary school was established within its walls. In 1877, Ms. Lucy Simms began her career inside of Long’s Chapel before moving on to the newly-built Effinger Street School in Harrisonburg. Many of the students in Zenda were illiterate because southern states had previously criminalized the education of slaves. This disability only further convinced blacks that education was vital to their success as free people. In addition to self-improvement, the opportunity to learn served as yet another expression of their new found freedom. The desire for education was particularly evident in Zenda when the 1880 Census revealed a 40% increase in the literacy rate within a decade. In 1882, Rockingham County built the “Athens School” in order to provide additional space for the growing community. Unfortunately, a decline in population forced the school to close its doors in 1925. The remaining residents were then forced to travel south to Harrisonburg in order to attend the all-black Effinger Street School.

Zenda’s chapel soon provided for the educational as well as the religious needs of the community when a primary school was established within its walls. In 1877, Ms. Lucy Simms began her career inside of Long’s Chapel before moving on to the newly-built Effinger Street School in Harrisonburg. Many of the students in Zenda were illiterate because southern states had previously criminalized the education of slaves. This disability only further convinced blacks that education was vital to their success as free people. In addition to self-improvement, the opportunity to learn served as yet another expression of their new found freedom. The desire for education was particularly evident in Zenda when the 1880 Census revealed a 40% increase in the literacy rate within a decade. In 1882, Rockingham County built the “Athens School” in order to provide additional space for the growing community. Unfortunately, a decline in population forced the school to close its doors in 1925. The remaining residents were then forced to travel south to Harrisonburg in order to attend the all-black Effinger Street School.

Today, only Long’s Chapel and the Wilson family homestead remain of what was once a vibrant community of hope. The Wilsons were one of the earliest families to settle in Zenda during the 1870s, and by 1940, they were the only people of color that remained. Their sturdy home has been continually occupied and well cared for ever since. Long’s Chapel, however, stood vacant and neglected for decades. Until very recently, its limestone supports were crumbling and the building was almost completely enveloped by brush.

Mr. Al Jenkins recalls discovering Long's Chapel for the first time

In 2004, a husband and wife from Charleston, South Carolina were vacationing in the Shenandoah Valley when they discovered this withered chapel on a self-guided tour of local history. Al and Robin Jenkins were captivated by the old church and the community of freed people that once congregated within its walls. They not only discovered a landmark in desperate need of preservation, but they unearthed a forgotten story that needed to be told. With little hesitation, the Jenkinses purchased the property and formed the “Long’s Chapel Preservation Society.” After more than a decade of tireless efforts, Long’s Chapel and the surrounding cemetery now stand as a visible testament to the hope and desires of the freed people of Rockingham County.

Rockingham County students know their local history!

This mural of Long's Chapel was produced by Mr. Routzahn's Virginia Studies class at Mountain View Elementary School.

Long’s Chapel is located east of Lacy Spring on Fridley’s Gap Road (see map below)

SOURCES:

Jones, Nancy B. Zenda: 1869-1930 - An African American Community of Hope. Bridgewater, Virginia: Good Printers, 2007.

Jones, Nancy B. Zenda: 1869-1930 - An African American Community of Hope. Bridgewater, Virginia: Good Printers, 2007.