The Establishment of Shenandoah National Park

Written by Kim Dean of East Rockingham High School

Correlation to the Virginia Standards of Learning: VS.2b, VS.9b, USII.6d, VUS.10a-d

Skyline Drive

Skyline Drive

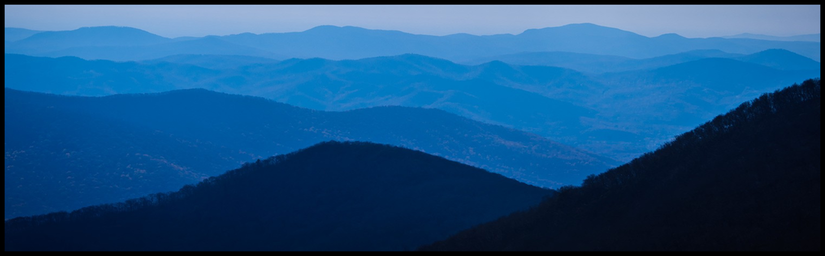

Over a million people come to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia each year to enjoy the beauty and recreational activities of Shenandoah National Park. They come from near and far to get away from the hustle and bustle of everyday modern life. Very few however, likely know that the trails they walk, the mountain spring waters they enjoy, and the hidden hollows that lie below Skyline Drive were all once home to a proud and resilient people. They were farmers, carpenters, blacksmiths, tanners, store keepers, and millers. They built schools, churches, and post offices, and they chose to live, work, worship, and die in a region of the Appalachians once thought untamable. The spirit of generations of mountain residents still lies deep within these Blue Ridge hills. The mountain once belonged to them, but more importantly, they belonged to the mountain.

The history of Shenandoah National Park began in the 1920s when most Americans were experiencing prosperity and enjoying the benefits of modern conveniences like electric appliances and automobiles. These modern conveniences provided Americans with more leisure time to enjoy picture shows, watch baseball games, and travel. Additional time to explore America’s wilderness led many to believe that the nation had a responsibility to preserve it for future generations. In 1916, the federal government established the National Park Service in order to protect and preserve these natural wonders for the enjoyment of all Americans. However, most early parks were located west of the Mississippi from lands already owned by the national government.

The history of Shenandoah National Park began in the 1920s when most Americans were experiencing prosperity and enjoying the benefits of modern conveniences like electric appliances and automobiles. These modern conveniences provided Americans with more leisure time to enjoy picture shows, watch baseball games, and travel. Additional time to explore America’s wilderness led many to believe that the nation had a responsibility to preserve it for future generations. In 1916, the federal government established the National Park Service in order to protect and preserve these natural wonders for the enjoyment of all Americans. However, most early parks were located west of the Mississippi from lands already owned by the national government.

Gov. Harry F. Byrd

Gov. Harry F. Byrd

In 1924, the National Park Service made a request to the Secretary of the Interior to establish a national park in the southern Appalachian Mountains. The goal was to create an eastern park in the western tradition of earlier parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone. Virginia and a number of other southern Appalachian states lobbied in Washington, D.C. to convince politicians that their state was the ideal location for a national park. Virginia’s efforts were successful, and in 1926, President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill to authorize the establishment of a national park in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

Many businessmen and politicians supported the park idea in an effort to entice tourists, increase revenue, renew Virginia’s prestige and conserve its natural history and resources. Governor Harry F. Byrd worked quickly with the Virginia General Assembly to establish the park within the state’s Blue Ridge Mountains. At the time, little thought was given to how this would impact the hundreds of families who called these mountains home. The years that followed were marked by confusion and heartache for many residents living in the midst of this dilemma.

Many businessmen and politicians supported the park idea in an effort to entice tourists, increase revenue, renew Virginia’s prestige and conserve its natural history and resources. Governor Harry F. Byrd worked quickly with the Virginia General Assembly to establish the park within the state’s Blue Ridge Mountains. At the time, little thought was given to how this would impact the hundreds of families who called these mountains home. The years that followed were marked by confusion and heartache for many residents living in the midst of this dilemma.

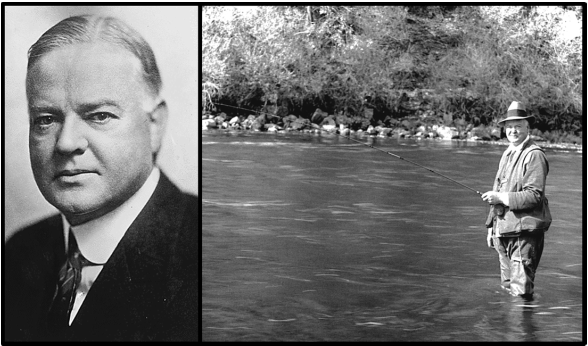

The displacement process was impacted by historic events and changes in presidential administrations. President Herbert Hoover envisioned a national park that allowed people to live within its boundaries - only residents who lived in the direct path of the proposed Skyline Drive would be forced to move. Hoover’s interest in the Blue Ridge Mountains began several years prior to the park’s establishment when he purchased land for his presidential retreat, Camp Hoover (more commonly known today as “Rapidan Camp”).

The use of federal funds to build a scenic highway in Virginia led to an increased interest in the proposed national park. The initial legislation authorizing the establishment of the park required the state of Virginia to purchase the needed properties and then cede them to the U.S. Department of Interior. The originial authorization for the park encompassed 521,000 acres, but the process proved to be more difficult and time consuming than expected. Some property owners refused to sell, rejected the assessment price, or simply had no plans for relocation. Early grassroots efforts by the Virginia Chamber of Commerce and other park promoters failed to raise sufficient funds to purchase the needed property from the mountain residents. These difficulties led the Virginia General Assembly to pass a blanket Condemnation Act in order to allow the State of Virginia to use the power of eminent domain to condemn all lands, homes, and buildings within the park boundaries. Despite a legal challenge, this action was subsequently upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

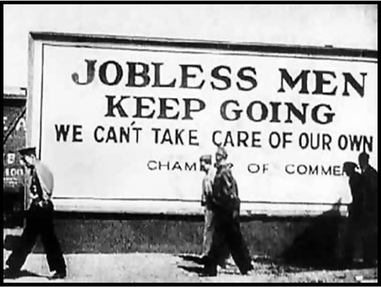

The unemployment rate reached 25% during the Great Depression

The unemployment rate reached 25% during the Great Depression

As the reigns of presidential power shifted during the election of 1932, so did the vision for Shenandoah National Park. Reckless over-speculation led to the 1929 stock market crash and the collapse of the nation’s banking system. During the Great Depression, the nation experienced record-breaking unemployment, bankruptcies, farm foreclosures, and homelessness. Unfortunately, this was also paralleled by an intense drought across the Great Plains that made it impossible to grow crops. The crusted topsoil gathered into massive clouds of dust that consumed mid-western states in what became known as the “Dust Bowl.” In addition to the drought, Virginia was plagued by a blight that completely decimated the chestnut trees that populated its forests. The elimination of this valuable hardwood was particularly damaging to the economy of Blue Ridge Mountain communities.

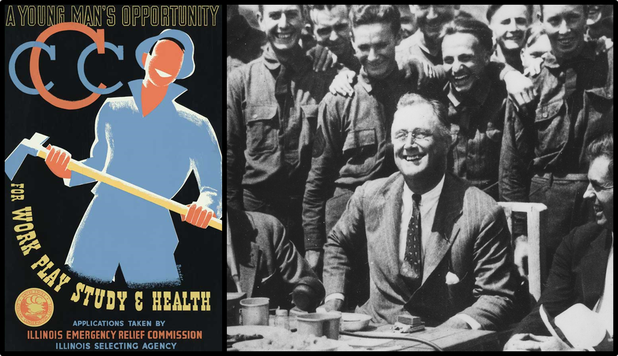

President Franklin D. Roosevelt developed a bold and comprehensive plan to provide relief, recovery, and reform programs designed to pull the nation out the Great Depression. These policies and programs were collectively known as the “New Deal.” One of Roosevelt’s most successful New Deal programs was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) - a public works program designed to promote conservation and provide jobs to young men. By 1935, the CCC consisted of over 500,000 young men who had built over 800 parks and planted nearly three million trees.

The continued need for labor made Shenandoah National Park a perfect location for the CCC program. Ten CCC camps operated in the park from 1933-1942, assisting with architectural, landscaping, and engineering projects. The CCC not only provided workers with much needed income to assist their struggling families, but it also offered them educational and vocational training to better prepare them for future employment.

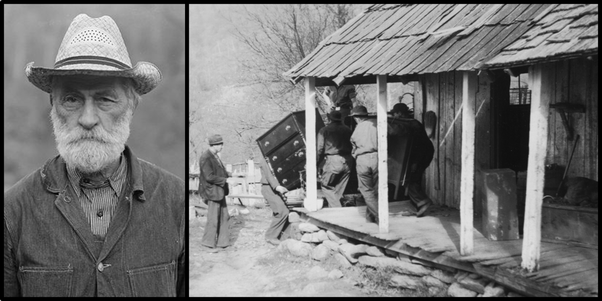

Work in the park throughout the Great Depression signaled to the remaining mountain residents that they would eventually be removed. Some families left voluntarily to seek better employment, some sold their land and moved from the mountain willingly, and some refused to sell and made no plans for relocation. In 1934, the Director of the National Park Service, Arno Cammerer, announced that all residents within park boundaries would have to vacate. In addition to this order, it was necessary to remove all traces of human occupation in order to restore the Blue Ridge Mountains to their natural state. To mountain residents, this meant that their homes, fields, barns, schools, and all other evidence of their presence would be erased.

Virginia ceded to the national government a total of 1088 land tracts that encompassed 181,578 acres across eight counties valued at $2.2 million dollars. In July of 1936, President Roosevelt dedicated the park at a ceremony held at Big Meadows. While the President ate lunch with the CCC boys, several hundred families were actually still living within the park boundaries. The relocation process continued for another two years. Some families qualified for the Resettlement Housing Program in various locations within surrounding counties. This process required them to pay rent over an extended period of time which eventually led to their ownership of the homestead. Only forty-three people were granted a “lifetime tenancy” based on personal situation and merit - most of these lived just inside the park boundary. Mrs. Annie Shenk, the last living resident within the park, died in 1979 at age 92.

The story of Shenandoah National Park is one which is bittersweet. Today, when visitors come to Shenandoah National Park, the mountain is still and quiet, undisturbed by the hustle and bustle of life below in the Valley. Those who dreamed of a national park in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, “to be set aside for all time as a reserve for the use and enjoyment of all people” can be assured that the mountain retains that purpose. The mountain residents whose final resting place is there are surrounded by peace and tranquility. The remnants of the people who once called the Blue Ridge their home now lie hidden within its hollows. The mountains hold the spirit and memory of those whose sacrifices allow future generations to enjoy the beauty of the majestic Blue Ridge.

"Now when the angels come

To take my soul to rest

They will find it in the park."

-John T. Nicholson, 1934

Blue Ridge Mountain Resident

SOURCES:

Engle, Reed. “Historical Overview.” Shenandoah National Park.

http://www.nps.gov/shen/historyculture/historicaloverview.htm

Horning, Audrey. In the Shadow of Ragged Mountain. Bridgewater, Virginia: Shenandoah National Park Association, 2004.

Lambert, Darwin. The Underlying Past of Shenandoah National Park. Boulder, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart, Inc. Publishers, 1989.

Engle, Reed. “Historical Overview.” Shenandoah National Park.

http://www.nps.gov/shen/historyculture/historicaloverview.htm

Horning, Audrey. In the Shadow of Ragged Mountain. Bridgewater, Virginia: Shenandoah National Park Association, 2004.

Lambert, Darwin. The Underlying Past of Shenandoah National Park. Boulder, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart, Inc. Publishers, 1989.