Elder John Kline: Peace Martyr of the Shenandoah Valley

Correlation to the Virginia Standards of Learning: VS.7a, USI.5a, USI.8d, VUS.6e

The Brethren faith emerged from the village of Schwarzenau in the German province of Westphalia during the Protestant Reformation. In 1708, a miller named Alexander Mack led four men and three women to break with accepted church practice by baptizing themselves in the waters of the Eder River. This group of dissenters rejected the practice of infant baptism as an act of coercion and asserted that adolescents and adults must willfully choose to be baptized as a covenant of Christian discipleship. The Brethren also practiced non-violence and refused to take part in the endless wars between the Protestant German states and Catholic France.

The Eder River in Schwarzenau, Germany

The Eder River in Schwarzenau, Germany

Persecution by the established and recognized churches (Roman Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed) led many of the Brethren to seek refuge in the New World. They initially found safe haven with the tolerant Quakers of Pennsylvania. The Quakers were non-violent Christians that had previously fled Europe in order to escape persecution by the Church of England. As a result of their experiences with European theocracy, the Quakers embraced the separation of church and state and established religious freedom throughout their New World colony. Within this environment of toleration, the Brethren were now free to practice “trine immersion” baptism (three full immersions to symbolize the holy trinity). As a result, their Pennsylvania neighbors began to refer to them as the “dunkers” (the term “dunker” is derived from the German word “tunken,” which means “to dip or submerge”).

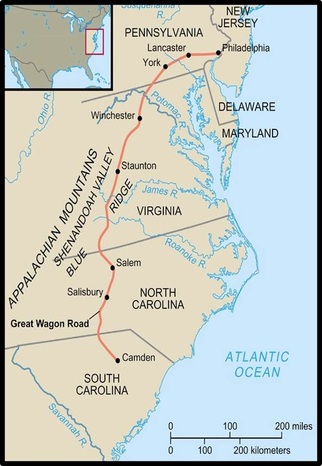

The "Great Wagon Road"

The "Great Wagon Road"

As settlement moved west across Pennsylvania, the formidable barrier of the Allegheny Mountains led many pioneers south to the Potomac River, and then west into the Great Valley of Virginia. From Harpers Ferry, settlers moved “up the Valley” by traveling against the northward flow of the Shenandoah River. The fertile valley they discovered between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains provided verdant land that was ideal for farming. Continued settlement from Pennsylvania and Western Maryland established a route through the Shenandoah Valley that later became known as the “Great Wagon Road.” Countless German and Scots-Irish settlers travelled this route during the mid-1700s in order to cross into the Virginia frontier (the Great Wagon Road later transformed into the “Valley Turnpike” during the mid-1800s, and it is known today as “Route 11”).

In 1811, the “Klein” family of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania followed the Great Wagon Road to Rockingham County, Virginia. Their oldest son, John, was fourteen when they settled on the west side of Linville Creek near a trading outpost later known as "Broadway." In addition to becoming a skilled farmer, young John also proved to be an avid reader and a disciplined student of the Bible, science, and history.

In 1811, the “Klein” family of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania followed the Great Wagon Road to Rockingham County, Virginia. Their oldest son, John, was fourteen when they settled on the west side of Linville Creek near a trading outpost later known as "Broadway." In addition to becoming a skilled farmer, young John also proved to be an avid reader and a disciplined student of the Bible, science, and history.

In 1818, John Kline married Anna Wampler, and they soon established a prosperous farm on the east side of Linville Creek. Four years later, John and Anna built a brick homestead near a continuous spring on a hillside above the creek. In addition to serving as living quarters, their new home was also designed to function as a Brethren meeting house. Three walls on the first level hung on hinges and could be raised for worship services and council meetings. As the congregation grew, Kline donated a sizable wooded lot on the eastern end of his property for the construction of a permanent meeting house and cemetery. This property later developed into the present-day Linville Creek Church of the Brethren.

In 1827, John Kline was called to serve as a church deacon. Three years later, he became a minister of the first degree, and in 1835, he was ordained as a church elder. His congregation continued to grow, but the Brethren “free ministry” system meant he still had to work his farm in order to maintain his livelihood. In addition to serving the parishioners of the Linville Creek congregation, Kline and his fellow elders traveled throughout the Shenandoah Valley in order to spread the faith. These mission trips later expanded into western Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana. In the twenty years between 1843 and 1863, it is estimated that Elder Kline traveled over 86,000 miles as a Brethren missionary. In December of 1850, Kline even made a trip to Washington, D.C., and was received at the White House by President Millard Fillmore.

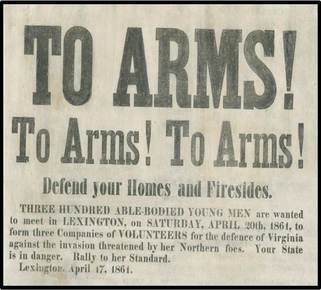

A call for milita volunteers - Lexington, Virginia

A call for milita volunteers - Lexington, Virginia

As the sectional crisis between the North and South deepened during the 1850s, Elder Kline feared that the peace-loving Brethren would be caught in the midst of future conflict. On New Year’s Day 1861, he wrote, “The year opens with dark and lowering clouds on our national horizon… Secession means war; and war means tears and ashes and blood. It means bonds and imprisonments, and perhaps even death to many in our beloved Brotherhood." The Brethren generally avoided politics, but they also believed that the principle of civil government was ordained by God. Therefore, many supported the Union and considered secession an act of rebellion against the design of Heaven. Elder Kline made the Brethren position clear when he wrote to Virginia Governor John Letcher that, “the General Government of the United States of America, constituted upon an inseparable union of the several states, had proved itself to be of incalculable worth to its citizens and the world, and therefore we, as a church and people, are heart and soul opposed to any move which looks toward its dismemberment.”

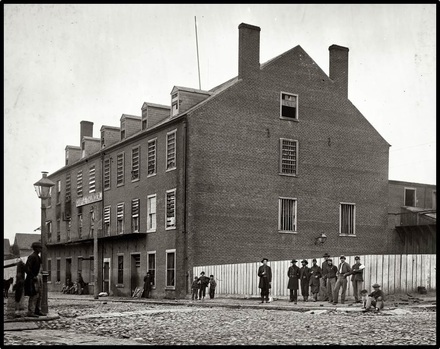

"Castle Thunder" - a former tobacco warehouse in Richmond that was converted into a Confederate prison camp for civilians. This photograph features Union soldiers in the foreground after the fall of Richmond during the spring of 1865.

"Castle Thunder" - a former tobacco warehouse in Richmond that was converted into a Confederate prison camp for civilians. This photograph features Union soldiers in the foreground after the fall of Richmond during the spring of 1865.

In addition to their opposition to slavery and secession, the Brethren doctrine of non-violence led them to oppose military service as well. When rumors spread of a Confederate conscription law during the Spring of 1862, about ninety Brethren and Mennonite men abandoned their homes in the Shenandoah Valley and fled west in order to escape from serving in the Confederate Army. About seventy of them were captured in the Allegheny Highlands of present-day West Virginia and were sent to the civilian prison camp in Richmond known as "Castle Thunder." A smaller group was later captured near the mountain town of Petersburg and brought back to a guard house in Mt. Jackson. At the same time, Elder Kline and several Mennonite and Brethren leaders were arrested and imprisoned in the jury room of the Rockingham County Courthouse because of their public opposition to military service. These prisoners served a two week sentence while Confederate officials questioned them about their religious beliefs.

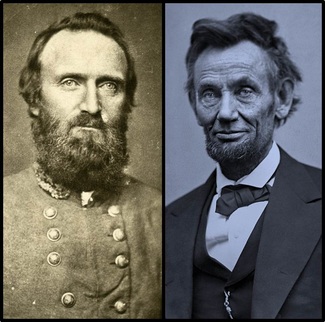

Confederate General "Stonewall Jackson" and Union President Abraham Lincoln

Confederate General "Stonewall Jackson" and Union President Abraham Lincoln

In a letter to Representative John B. Baldwin of Virginia, Kline explained, “we are a non-combatant people. We believe most conscientiously that it is the doctrine taught by our Lord in the New Testament which we feel bound to obey…Hence we feel rather to suffer persecution, bonds, and if need be death than break the vow made to our God.” After continued appeals, the Confederate Congress in Richmond passed an exemption act that allowed conscientious objectors to pay a $500 fine plus two percent of their property value or provide an able-bodied substitute to serve in their place.

Union as well as Confederate leaders later expressed public support for religious exemption laws. President Lincoln declared, “These people do not believe in war. People who do not believe in war make poor soldiers. Besides, the attitude of these people has always been against slavery. If all our people had held the same views about slavery as these people hold there would be no war. These are largely a rural people, sturdy and honest. They are excellent farmers. The country needs good farmers fully as much as it needs good soldiers.” General Stonewall Jackson expressed a similar view from the Confederate side when he wrote about the Brethren refusal to shed blood. He recalled, “There lives a people in the Valley of Virginia that are not hard to bring to the army. While there, they are obedient to their officers. Nor is it difficult to have them take aim, but it is impossible to get them to take correct aim. I, therefore, think it better to leave them at their homes that they may produce supplies for the army.”

Union as well as Confederate leaders later expressed public support for religious exemption laws. President Lincoln declared, “These people do not believe in war. People who do not believe in war make poor soldiers. Besides, the attitude of these people has always been against slavery. If all our people had held the same views about slavery as these people hold there would be no war. These are largely a rural people, sturdy and honest. They are excellent farmers. The country needs good farmers fully as much as it needs good soldiers.” General Stonewall Jackson expressed a similar view from the Confederate side when he wrote about the Brethren refusal to shed blood. He recalled, “There lives a people in the Valley of Virginia that are not hard to bring to the army. While there, they are obedient to their officers. Nor is it difficult to have them take aim, but it is impossible to get them to take correct aim. I, therefore, think it better to leave them at their homes that they may produce supplies for the army.”

|

|

Despite the protection of the exemption laws, Confederate partisans often harassed the Brethren and called their loyalty into question. Elder Kline expressed this concern in a letter to the Confederate Congress. He wrote, “under the excitement of the hour, indiscreet, and inconsiderate persons have preferred the charge of disloyalty against our Churches. This charge has not the semblance of truth, in fact, and has doubtless originated from our faith against bearing arms.” |

Despite evidence to the contrary, rumors began to spread that Elder Kline was secretly serving as a Union spy. With churches spread from Tennessee to Indiana, Elder Kline had to obtain special permission to cross between Union and Confederate lines in order to manage church affairs. These forays into enemy territory led many Confederate sympathizers to question his loyalty. Two days before his sixty-seventh birthday in mid-June, Elder Kline visited an ill congregation member about four miles west of his home. Following his visit, he rode up a tree-lined ridge where an assassin’s bullet mortally wounded him, knocking him from his horse. A couple of Confederate irregulars who laid the ambush finished their deed by a shot to his chest. He may have died on that ridge, but his spirit continues to live on as a martyr for peace.

One month before his death, Elder Kline gave a sermon at the annual meeting of the Brethren in Hagerstown, Indiana that ended with the following message: “Possibly you may never see my face or hear my voice again. I am now on my way back to Virginia, not knowing the things that shall befall me there. It may be that bonds and afflictions abide me. But I feel that I have done nothing worthy of bonds or of death; and none of these things move me; neither count I my life dear unto myself, so that I may finish my course with joy, and the ministry which I have received of the Lord Jesus, to testify the Gospel of the grace of God.”

SOURCES:

Bowman, Rufus David. The Church of the Brethren and War. Elgin, Illinois: Brethren Publishing House, 1944.

Funk, Benjamin. Life and Labors of Elder John Kline: The Martyr Missionary. 2008. TS. Bibliobazaar, United States.

Nair, Charles E., Rev. John Kline Among His Brethren: Or How He Filled His Place. 2014. TS. Remembering John Kline's Life: 150 Years Later, Broadway, Virginia.

Wust, Klaus G. "Elder John Kline: A Life of Pacifism Ended in Martyrdom." Virginia Cavalcade Autumn 1964: Vol. 14:2. Print.

Bowman, Rufus David. The Church of the Brethren and War. Elgin, Illinois: Brethren Publishing House, 1944.

Funk, Benjamin. Life and Labors of Elder John Kline: The Martyr Missionary. 2008. TS. Bibliobazaar, United States.

Nair, Charles E., Rev. John Kline Among His Brethren: Or How He Filled His Place. 2014. TS. Remembering John Kline's Life: 150 Years Later, Broadway, Virginia.

Wust, Klaus G. "Elder John Kline: A Life of Pacifism Ended in Martyrdom." Virginia Cavalcade Autumn 1964: Vol. 14:2. Print.