The Burning of the Shenandoah Valley: September 26th-October 8th, 1864

Correlation to the Virginia Standards of Learning: VS.7b, USI.9f, VUS.7d

The Shenandoah Valley is a vast agricultural heartland situated between the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and Allegheny Mountains to the west. The Valley extends 125 miles from just north of Lexington to Harpers Ferry, where the Shenandoah River joins with the waters of the Potomac. This fertile region served as the “breadbasket” of the Confederacy during the Civil War as a major producer of wheat, corn, and various types of livestock. These provisions were invaluable in sustaining the Confederate army as it struggled to fight their well-supplied Union adversary. Virginia’s direct proximity to Washington, D.C. also made the Valley a natural invasion route into enemy territory. For example, Stonewall Jackson took the offensive west of the Blue Ridge during the Valley Campaign of 1862, and Robert E. Lee moved Confederate forces through the Valley during the Gettysburg Campaign of 1863.

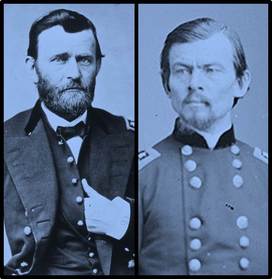

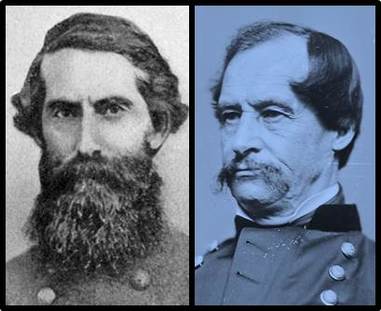

Union Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Franz Sigel

Union Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Franz Sigel

In March of 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant led the Union Army of the Potomac to invade central Virginia and attack Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. While focusing on Lee, Grant sent General Franz Sigel and the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah (9,000 men) across the Blue Ridge Mountains in order to invade the Valley and destroy the Confederate supply center in Staunton. On May 15th, Sigel was attacked by a force of 5,300 Confederates under the command of General John C. Breckinridge near the town of New Market. Despite being outnumbered by almost two to one odds, the Confederates fought bitterly in the rain and drove the Union Army across the North Fork of the Shenandoah River. The Southerners were so desperate for men that the cadets of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) were called upon to march north from Lexington in order to help defend the Valley.

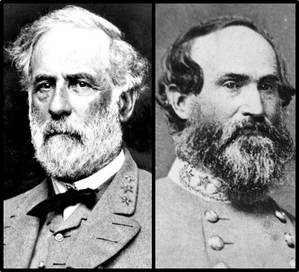

Confederate General "Grumble" Jones and Union General David Hunter

Confederate General "Grumble" Jones and Union General David Hunter

Frustrated by the inexplicable Union defeat in the Battle of New Market, Grant replaced Sigel with General David Hunter and ordered him to resume the march “up” the Valley (the northern flow of the Shenandoah River reverses geographic terminology, thus moving “up the Valley” means heading south, while “down the Valley" means heading north). General Hunter advanced south past Harrisonburg and turned east toward Port Republic. In an attempt to protect Staunton, Confederate forces under the command of William E. “Grumble” Jones took up position next to a bend in Middle River near the village of Piedmont in northeast Augusta County. After sustaining two Union assaults, “Grumble” Jones attempted to reorganize his men for a counter-attack, but inadvertently created a gap in Confederate line in the process. Hunter quickly exploited this vulnerability and sent an entire brigade into the fray. Jones tried to rally his men, but suffered a direct shot to the head and was killed instantly. The Confederate line completely collapsed, and Jones’ army temporarily retreated to Fishersville. Staunton fell to Hunter’s forces on June 6th, but the Confederates in Fishersville quickly moved into Rockfish Gap east of Waynesboro in order to prevent the Union forces from crossing Afton Mountain and seizing the Virginia Central Railroad in Charlottesville.

Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Jubal Early

Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Jubal Early

With the Blue Ridge crossing blocked, General Hunter continued the Union advance south toward Lexington. On June 12th, Union troops ransacked Washington College, set fire to the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), and destroyed the home of former Governor, John Letcher. General Robert E. Lee correctly predicted that Hunter would strike next at the Confederate supply center in Lynchburg. Despite his vulnerable position in the trenches at Cold Harbor near Richmond, Lee sent 8,000 men under the command of General Jubal Early west toward Lexington in order to reinforce the Confederate force in the Valley. Hunter attacked on June 17th, but failed to dislodge the Confederate position. The Battle of Lynchburg convinced Hunter that he was greatly outnumbered, and he decided to retreat back across the Blue Ridge. With over 12,000 troops under his command, General Early took the offensive and drove Hunter all the way into the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia. With no Union force to oppose him, Early reclaimed the Valley and marched north along the Valley Pike in order to threaten Washington, D.C. In retaliation for Hunter’s destruction of Lexington, Early sent his cavalry across the Potomac to burn the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

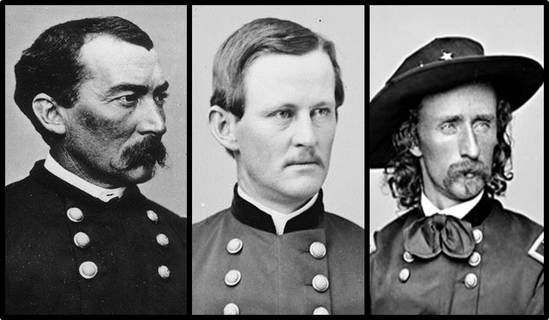

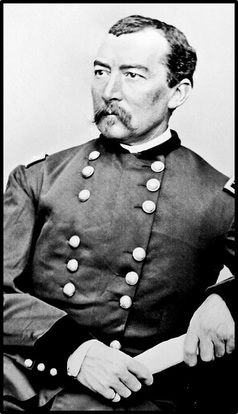

Union General Phillip Sheridan

Union General Phillip Sheridan

Frustrated by another Confederate invasion through the Valley, Grant sent a telegram to the Union Army Chief-of-Staff, Henry Halleck, and instructed him to assemble a force that would "eat out Virginia clean and clear …so that crows flying over it …will have to carry their own [food] with them." When Hunter failed to pursue Early, Grant replaced him with his young and aggressive cavalry commander, 33 year-old Phillip Sheridan. Grant’s orders to Sheridan were clear: “give the enemy no rest…do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. Carry off [live]stock of all descriptions, and negroes, so as to prevent further planting. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.”

General Sheridan resumed the offensive and defeated Jubal Early’s Confederate force at the Battle of Third Winchester on September 19th, and again at the Battle of Fisher’s Hill near Front Royal on September 22nd. The badly outnumbered Confederates forced Early to retreat up the Valley to the protection of Brown’s Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains east of Port Republic. Sheridan pursued him up the Valley and occupied the town of Harrisonburg on September 25th. Satisfied that he had soundly defeated Early, Sheridan proposed a plan to destroy the bounty of the Shenandoah Valley by systematically destroying its crops, slaughtering its livestock, and setting fire to the countless barns and mills that dotted its fertile landscape.

General Sheridan resumed the offensive and defeated Jubal Early’s Confederate force at the Battle of Third Winchester on September 19th, and again at the Battle of Fisher’s Hill near Front Royal on September 22nd. The badly outnumbered Confederates forced Early to retreat up the Valley to the protection of Brown’s Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains east of Port Republic. Sheridan pursued him up the Valley and occupied the town of Harrisonburg on September 25th. Satisfied that he had soundly defeated Early, Sheridan proposed a plan to destroy the bounty of the Shenandoah Valley by systematically destroying its crops, slaughtering its livestock, and setting fire to the countless barns and mills that dotted its fertile landscape.

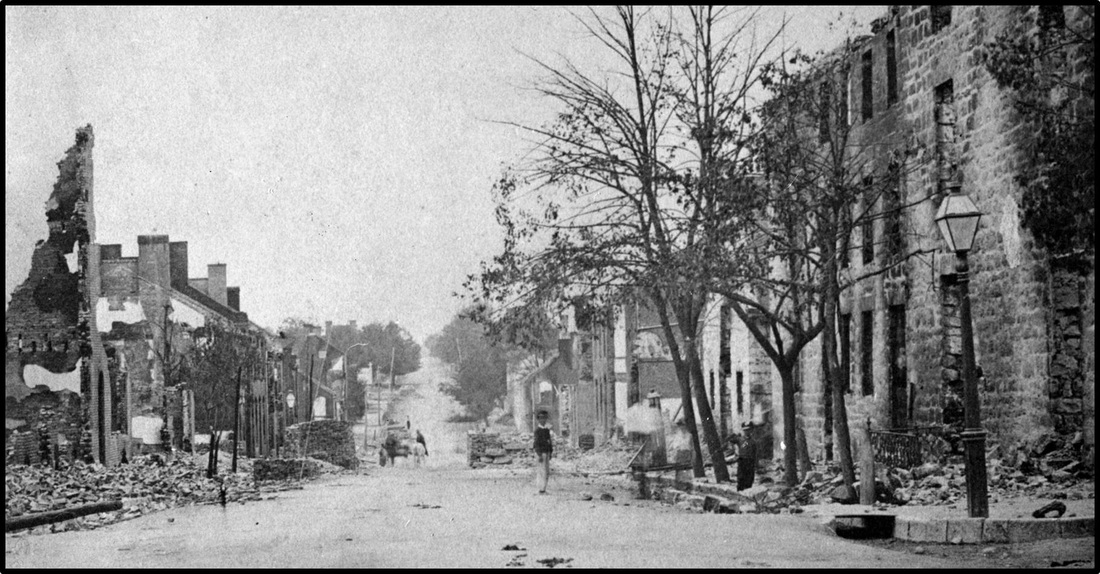

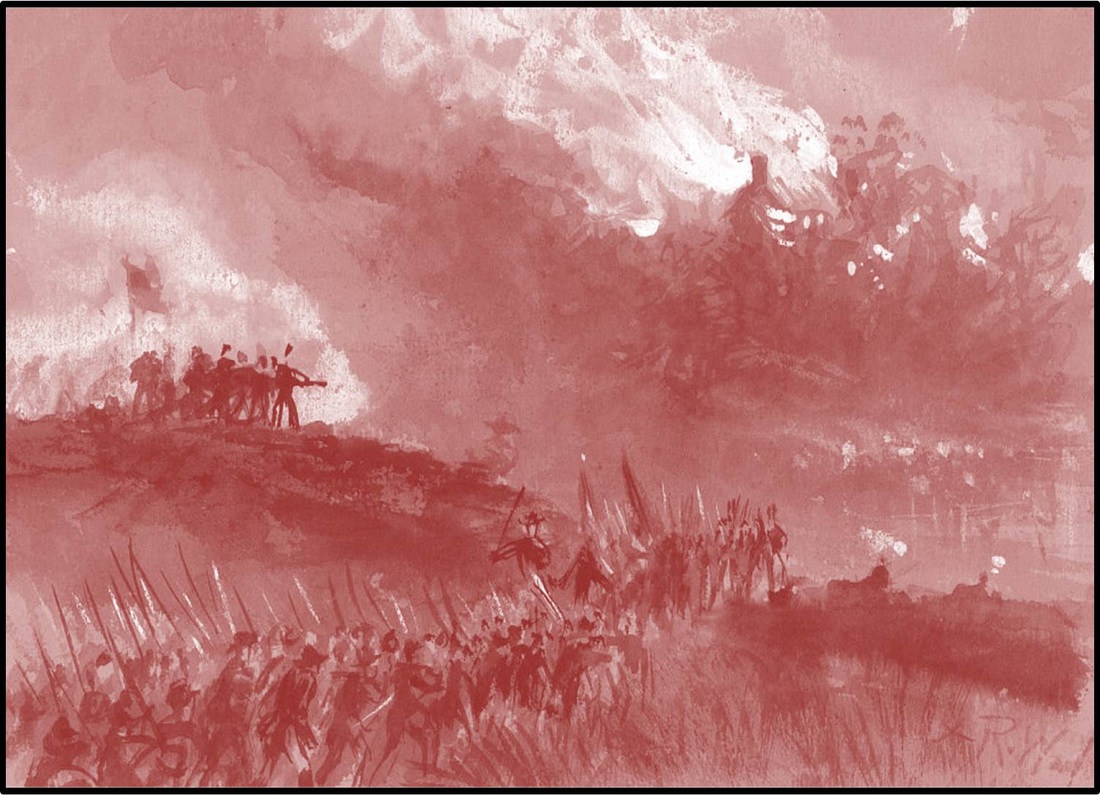

For the thirteen days between September 26th and October 8th, Union forces fanned across the Valley on a path of unspeakable destruction. With Early pinned down in Brown’s Gap, Sheridan’s forces spread out from Harrisonburg and wreaked havoc in northern Augusta and southern Rockingham County. The skies darkened as plumes of smoke rose from countless barns, mills, and corncribs. A Confederate scout observing the burning from a hillside near Timberville wrote, “[F]or miles glowing spots of burning visible – tongues of flame still licking about heavy beams and sills – flames sometimes of many colors from burning grain and forage…It seemed to us the firmament had descended –the stars had fallen...Think of it we said: Looking downward to see the stars!...Until this day, no such desolation had been witnessed since the war began.”

Given that General Sheridan’s orders originated from his headquarters in Harrisonburg, much of the destruction was concentrated in Rockingham County. After spending more than a week in the surrounding area, Sheridan divided his force into thirds and moved down the Valley, setting fires and slaughtering livestock all the way to Strasburg. Sheridan led his infantry north on the Valley Pike while dispatching two of his cavalry commanders to lead their forces on parallel routes to the west; General Wesley Merritt took the middle route on the Broadway Road (present-day Route 42), while General George Armstrong Custer took the “back road” through Singers Glen and Brocks Gap. On October 7th, Sheridan reported to General Grant from Woodstock that, “the whole country, from the Blue Ridge to the North Mountain, had been made untenable for a rebel army. I have destroyed over two thousand barns filled with wheat, hay, and farming implements; over seventy mills filled with wheat, and flour; four herds of cattle have been driven before the army, and not less than three thousand sheep have been killed and issued to the troops.” This infamous act of bringing war to the civilians of the Shenandoah Valley is known locally as “The Burning.”

SOURCES:

Heatwole, John L. The Burning: Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing, 1998.

1864: The Valley Aflame. Staunton, Virginia: Lot's Wife Publishing, 2005.

Heatwole, John L. The Burning: Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing, 1998.

1864: The Valley Aflame. Staunton, Virginia: Lot's Wife Publishing, 2005.