Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign and the Battles of Cross Keys & Port Republic

Correlation to the Virginia Standards of Learning: VS.7b, USI.9d-e, VUS.7b

Stonewall Jackson Statue at Manassas Battlefield

Stonewall Jackson Statue at Manassas Battlefield

The first battle of the American Civil War occurred on the banks of Bull Run Creek near Manassas, Virginia. The Union assault at the Confederate left flank was successful until an eccentric professor named Thomas J. Jackson led the Virginia soldiers of the 1st Brigade into the fray. Jackson had previously taught physics and artillery tactics at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), and he now took great pride in placing thirteen cannons on top of Henry Hill in order to help solidify the center of the Confederate line. Jackson’s infantrymen fought bravely while bullets hissed by their firm and grim-faced commander. Inspired by his resolve, General Barnard Bee of South Carolina tried to rouse his men by exclaiming, “Look, there stands Jackson like a stonewall – rally behind the Virginians!”

The tide of battle shifted late in the day when Confederate reinforcements arrived by rail from the Shenandoah Valley under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston and Colonel Jubal Early. After fourteen hours of fighting under a blazing July sun, the sight of fresh Confederate troops completely sank the Union morale. Their line broke and the Union retreat turned into a full rout as they fled back to Washington, D.C. Confederate soldiers not only took pride in their victory, but word spread quickly about the stand of the Virginia Brigade and the “stonewalled” rigidity of their commander.

The tide of battle shifted late in the day when Confederate reinforcements arrived by rail from the Shenandoah Valley under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston and Colonel Jubal Early. After fourteen hours of fighting under a blazing July sun, the sight of fresh Confederate troops completely sank the Union morale. Their line broke and the Union retreat turned into a full rout as they fled back to Washington, D.C. Confederate soldiers not only took pride in their victory, but word spread quickly about the stand of the Virginia Brigade and the “stonewalled” rigidity of their commander.

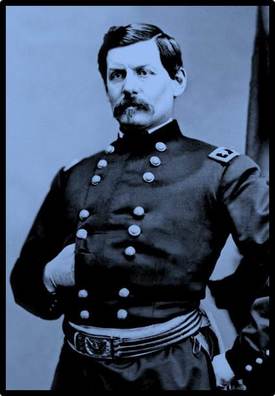

Union General George McClellan

Union General George McClellan

The Union disaster at First Manassas led President Lincoln to remove General Irvin McDowell from command and replace him with the reputable and haughty George McClellan. Despite the President’s desire to strike a blow against the Confederates, General McClellan temporarily retired from the field and spent the Fall of 1861 re-training his men and restoring discipline within the Union ranks. By the Spring of 1862, McClellan’s “Army of the Potomac” had been transformed into a mighty fighting force of over 120,000 men. General McClellan developed a bold plan to move this massive force down the Potomac River, land it on the York-James Peninsula, and march west along the James River in order to attack the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Heavy spring rains flooded the rivers and streams, turning Virginia roads into muddy bogs. McClellan was further delayed by 11,000 Confederate troops entrenched around Yorktown in some of the same fortifications that had been captured by George Washington and the Continental Army eighty years beforehand. McClellan outnumbered the opposing force by more than 10 to 1, but the overly-cautious Union General ordered his men to entrench and prepare for a siege.

Heavy spring rains flooded the rivers and streams, turning Virginia roads into muddy bogs. McClellan was further delayed by 11,000 Confederate troops entrenched around Yorktown in some of the same fortifications that had been captured by George Washington and the Continental Army eighty years beforehand. McClellan outnumbered the opposing force by more than 10 to 1, but the overly-cautious Union General ordered his men to entrench and prepare for a siege.

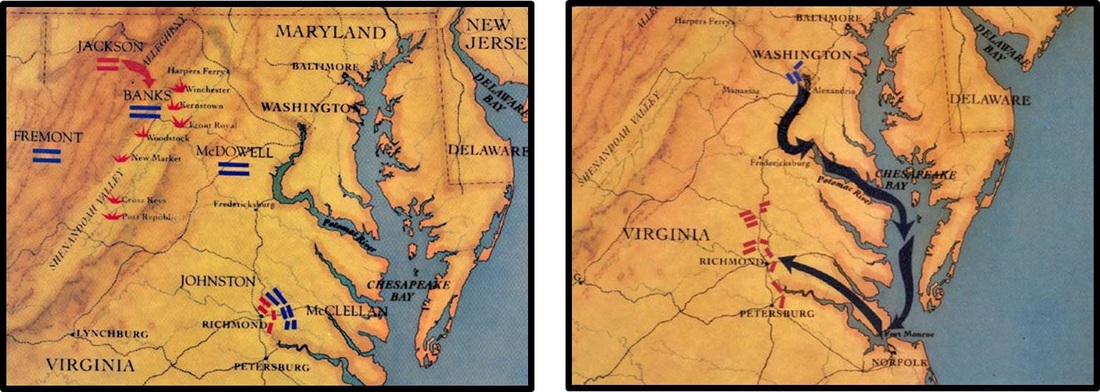

Jackson's Valley Campaign |

McClellan's Peninsula Campaign |

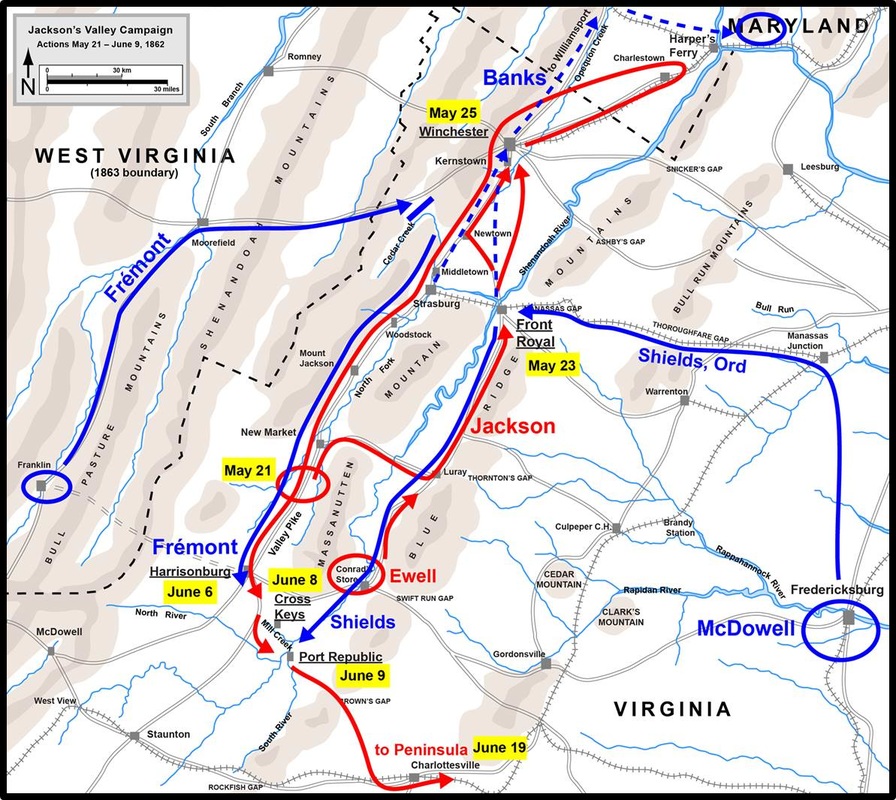

As McClelland struggled at Yorktown, Stonewall Jackson viewed the swelled banks of the Shenandoah River from the small village of Conrads Store (present-day Elkton). Jackson had recently been placed in command of all forces west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, but Confederate authorities in Richmond had ordered him to remain on the defensive in order to protect supply lines and prevent the further advance of Union troops “up” the Shenandoah Valley (the northern flow of the Shenandoah River reverses geographic terminology, thus moving “up” the Valley means heading south, while “down” the Valley means heading north).

As Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston became increasingly preoccupied with McClellan’s invasion, Robert E. Lee (then serving as President Jefferson Davis’s military advisor), eagerly assumed responsibility for coordinating with Stonewall Jackson in the Valley. Lee admired Jackson’s tenacity and he encouraged him to take the offensive and move “down” the Valley toward the Union forces near Harpers Ferry. This would not only protect the rich agricultural abundance of the Shenandoah Valley, but would also divert Union troops away from Richmond in order to protect Washington, D.C. from a Confederate offensive west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. This strategic diversion became known as Jackson’s “Valley Campaign” of 1862.

The remnants of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

The remnants of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

In an effort to deceive Union forces near Harrisonburg, Jackson marched south from Conrad’s Store, crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains at Browns Gap, and briefly descended into the Virginia Piedmont, only to board the Central Virginia Railroad at Mechum’s River Station and secretly pass back through the mountains via the newly constructed Blue Ridge Tunnel near Crozet. Jackson’s Army disembarked from the train at the Confederate supply center in Staunton and marched west into Highland County in order to engage the Union Army of General John C. Fremont. On May 8th, Jackson routed Fremont at the Battle of McDowell and pursued his force for thirty miles north to the town of Franklin before turning back and returning to Staunton.

Jackson’s “foot cavalry” then turned north and skirted east of the Massanutten Mountain, marched undetected through the Page Valley, and defeated the Union Army of Nathaniel Banks at Front Royal on May 23rd and again at Winchester on May 25th. Despite the temptation to allow his victorious army much needed rest, Jackson pursued Banks all the way to Harpers Ferry.

Union General James Shields

Union General James Shields

Frustrated by the loses in the Valley, as well as the lack of progress on the Peninsula, President Lincoln wired General McClellan, “the enemy is moving north in a sufficient force to drive Banks.…I think the time is near when you must either attack Richmond or give up the job and come to the defence of Washington.” The War Department in Washington, D.C. was astounded by Jackson’s success in the lower Valley (i.e. northern Valley). Instead of sending reinforcements to Richmond to assist McClellan, General Irvin McDowell was ordered to remain in Fredericksburg and send 20,000 of his men under the command of General James Shields west into the Valley to pursue Jackson.

Union General John C. Fremont

Union General John C. Fremont

When Jackson threatened Harpers Ferry, President Lincoln ordered General Fremont to drive east out of the Allegheny Mountains as General Shields moved west across the Blue Ridge in an effort to trap Jackson in the lower Valley near Strasburg. When notified of the two forces advancing to his rear, Jackson correctly predicted their rendezvous point, and swiftly marched his army south in an effort to avoid the trap set by Fremont and Shields. Despite his precarious position, Jackson’s “foot cavalry” endured two days of twenty mile marches and narrowly slipped between the two Union armies on June 1st. While Fremont pursued Jackson on the west side of Massanutten Mountain, Shields paralleled his movements on the east side of the range in the hopes of surrounding Jackson near Harrisonburg.

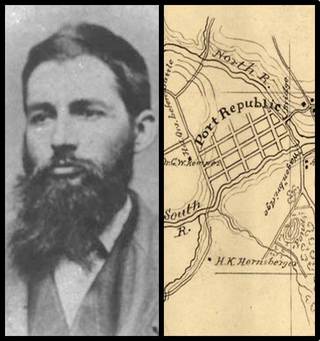

Jedediah Hotchkiss and his map of Port Republic

Jedediah Hotchkiss and his map of Port Republic

Late spring rains fell as Jackson reached New Market on June 4th. That night he summoned his chief cartographer, Jedidiah Hotchkiss, in order to examine the eight foot map of the Shenandoah Valley that he had drawn for the Campaign. Jackson pointed to a small village east of Harrisonburg at the headwaters of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River and stated, “that is where I will make my stand.” At the tip of the General’s finger, Hotchkiss read the words, “Port Republic.”

The village of Port Republic was a bustling river town at the point where South River flows into North River to form the South Fork of the Shenandoah. Jackson’s daring cavalry commander, General Turner Ashby, prevented the pursing Union armies from uniting forces by burning the remaining South Fork bridges at Luray and Conrads Store. This maneuver enabled Jackson to position himself at Port Republic’s North River Bridge and fight the Union armies in piecemeal fashion. If the need arose, Port Republic’s direct proximity to Browns Gap provided Jackson with an ideal escape route over the Blue Ridge Mountains and into the Virginia Piedmont. Spring flooding and swift water only further strengthened Jackson’s position by preventing the construction of Union pontoon bridges.

The village of Port Republic was a bustling river town at the point where South River flows into North River to form the South Fork of the Shenandoah. Jackson’s daring cavalry commander, General Turner Ashby, prevented the pursing Union armies from uniting forces by burning the remaining South Fork bridges at Luray and Conrads Store. This maneuver enabled Jackson to position himself at Port Republic’s North River Bridge and fight the Union armies in piecemeal fashion. If the need arose, Port Republic’s direct proximity to Browns Gap provided Jackson with an ideal escape route over the Blue Ridge Mountains and into the Virginia Piedmont. Spring flooding and swift water only further strengthened Jackson’s position by preventing the construction of Union pontoon bridges.

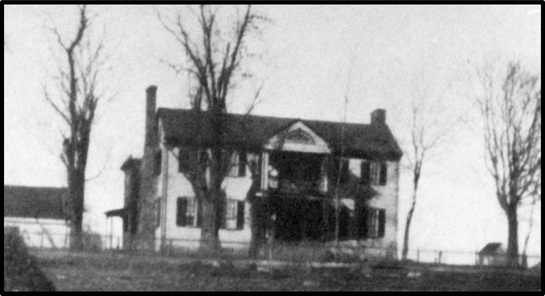

Madison Hall - the home of Dr. George Whitfield Kemper in 1862

Madison Hall - the home of Dr. George Whitfield Kemper in 1862

On June 6th, Jackson marched southeast from Harrisonburg and crossed the North River Bridge into Port Republic. He established his headquarters on a knoll above the southwestern edge of the village at the Madison Hall estate of Dr. George Whitfield Kemper. Jackson’s supply train of wagons was parked immediately south of Madison Hall on a road that led to the Confederate supply center in Staunton. Despite the natural defensive strength of Jackson’s surroundings, the great majority of his forces were encamped on the left bank of North River near Mill Creek.

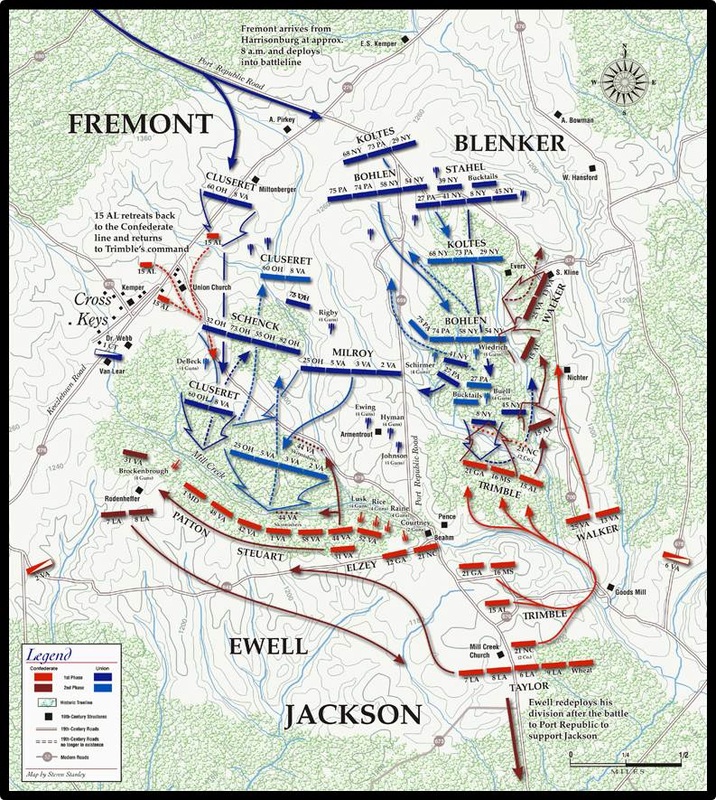

The Battle of Cross Keys - June 8th, 1862

Confederate General Isaac Trimble

Confederate General Isaac Trimble

Stonewall Jackson rose on the morning of Sunday, June 8th with the anticipation of celebrating the Sabbath. At approximately 8:30 AM, an artillery shell broke the morning silence as Union cavalry splashed across South River and into the streets of Port Republic. Jackson narrowly escaped capture as he galloped down Main Street and across the North River Bridge. The Union raiders advanced toward the southwest corner of the village in order to capture the Confederate supply train, but a small band of infantrymen and the newly formed Charlottesville Artillery made a brief stand around Madison Hall until Jackson rallied troops to retake the bridge and drive the raiders back across the South River.

Just as Jackson regained control of the village, cannon boomed to the west as the Union Army of John C. Fremont attacked the Confederate forces stationed near Cross Keys. General Richard Ewell positioned three Confederate brigades across the Port Republic Road on a wooded hillside that overlooked Mill Creek. Despite an exposed left flank near the Union Church in Cross Keys, Fremont decided to attack the Confederate right flank that was commanded by the feisty and aggressive General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble.

Just as Jackson regained control of the village, cannon boomed to the west as the Union Army of John C. Fremont attacked the Confederate forces stationed near Cross Keys. General Richard Ewell positioned three Confederate brigades across the Port Republic Road on a wooded hillside that overlooked Mill Creek. Despite an exposed left flank near the Union Church in Cross Keys, Fremont decided to attack the Confederate right flank that was commanded by the feisty and aggressive General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble.

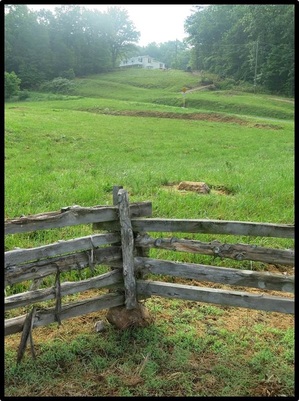

Worm fence at the crest of the hill above the Widow Pence Farm.

Worm fence at the crest of the hill above the Widow Pence Farm.

General Trimble was a feisty and obstinate old man that often struggled with accepting the authority of superiors many years his junior. Without orders, General Trimble boldly moved his men across Mill Creek, advanced past the Widow Pence Farm, and took position at a fence that stood just behind the crest of the hill. Realizing the value of their position, the eager Confederates crowded the line and staggered two-deep in some places. Infantrymen further masked their position by gathering leaves to pile into the lower planks of the fence. The men also amplified their firepower by jamming solid rounds as well as buckshot down the muzzle of their outdated smooth-bore muskets (a practice known as firing with “buck and ball”).

Tragically, Union General Julius Stahel advanced toward the fence line without the aid of skirmishers to scout the enemy position. Stahel unknowingly marched his men into a perfect deadfall. The 8th New York regiment had the unfortunate duty of leading this blind advance toward the concealed Confederates. An Alabamian lying behind the fence recalled, “They advanced with such precision, keeping the step, and their line was so well dressed that it was a matter of comment afterwards among our officers, but poor fellows, they did not know what was in store for them behind that fence.”

Tragically, Union General Julius Stahel advanced toward the fence line without the aid of skirmishers to scout the enemy position. Stahel unknowingly marched his men into a perfect deadfall. The 8th New York regiment had the unfortunate duty of leading this blind advance toward the concealed Confederates. An Alabamian lying behind the fence recalled, “They advanced with such precision, keeping the step, and their line was so well dressed that it was a matter of comment afterwards among our officers, but poor fellows, they did not know what was in store for them behind that fence.”

Trimble’s men first saw the tips of Union bayonets appear on the horizon as the 8th New York gradually started to crest the gentle slope of the hillside (pictured below). The Confederates held their fire as their enemy slowly came into focus. The advancing Federals got within 40 yards when a sheet of fire erupted from the bottom of the fence. A singular volley of gunfire killed or wounded over 300 men in just mere seconds. A young Georgian recalled, “The dead and wounded Yankees [were] lying on the field as thick as black birds.” General Trimble later boasted that the “deadly fire…dropp[ed] the deluded victims of Northern fanaticism and misrule by the score.” However, like many of his men, Trimble also admitted that his opponent’s “gallantry deserved a better fate.”

The Confederates eagerly pursued the fleeing Union soldiers as they fell back from the fence. General Trimble advanced on them for another mile before he fell back to his original position. The Union retreat forced General Fremont to call back his other regiments in order to maintain his overall line of defense. This turn of events completely sank the Union initiative, and the battle lingered on with only brief bouts of artillery fire. When General Ewell declined Trimble’s request to launch a counter-offensive, the stubborn old man requested to ride to Port Republic in order to take the matter before General Jackson. Trimble pled his case, but Jackson coolly reminded him of the chain of command and encouraged him to “consult General Ewell and be guided by him." Jackson's plans for the following day would move the army in the opposite direction toward Port Republic in order to attack the Union Army of James Shields.

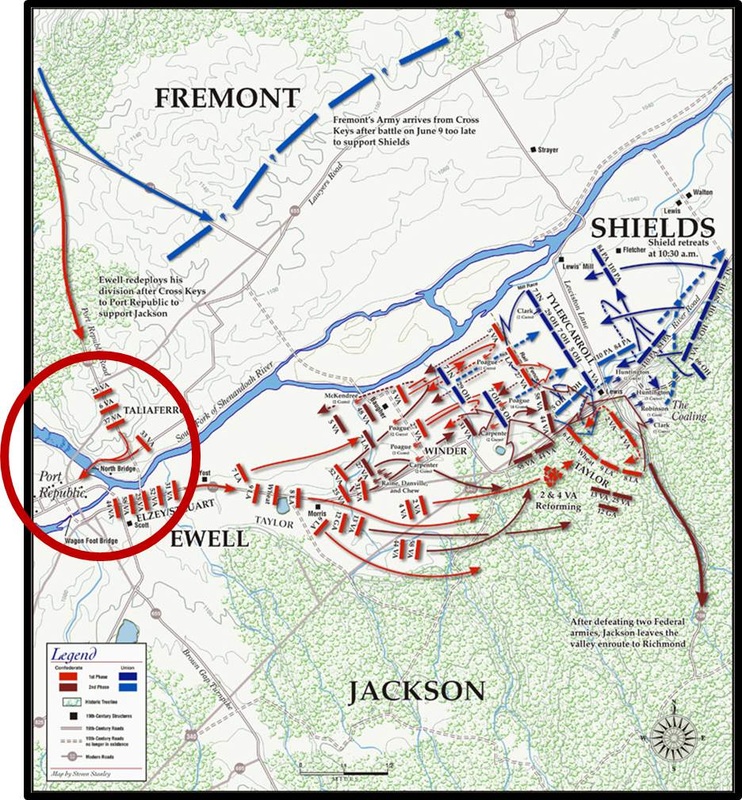

The Battle of Port Republic - June 9th, 1862

Union General Erastus Tyler

Union General Erastus Tyler

As the guns fell silent at Cross Keys, Jackson spent the night of June 8th planning for an attack against the Union forces northeast of Port Republic. Brigadier General Erastus Tyler had taken up position along the Lewiston Lane that ran east from the South Fork, across a broad river plain, to the top of a clear-cut hillside that jutted out from the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains. This position was known as the “Coaling” because the timber was cut and burned in order to make charcoal to fuel the Mount Vernon Furnace in Browns Gap. Union forces bolstered the position by placing six pieces of artillery on top of the hill in order to command the broad river plain that lay between them and the advancing Confederates.

The Battle of Port Republic commenced on the morning of June 9th when Jackson ordered General Sydney Winder and the Stonewall Brigade to cross South River, march northeast, and attack the Union line along the Lewiston Lane. When that effort stalled, General Richard Taylor and three regiments of Louisiana soldiers were sent into the woods at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains in order to flank the Coaling and capture the Union artillery. Just as Union troops counter-attacked Winder’s men in the river plain, Taylor’s Louisianans emerged from the woods and charged up the side of the Coaling. One veteran wrote, “The Louisianans dashed forward; the wild spirit of the men found vent in one loud, prolonged yell, which ran along the entire line as an electric current.” Union infantrymen fired in vain as the artillerymen lowered the cannon and fired canister rounds into the face of the charging Confederates. Countless men fell before the guns as the Louisianans swarmed the position. A brief moment of hand-to-hand combat ensued as swords, bayonets, and fists were unleashed across the smoky hillside.

The "Coaling"

The "Coaling"

A Louisianan recalled, “Men ceased to be men. They cheered and screamed like lunatics – they fought like demons – they died like fanatics…It was not war on that spot. It was a pandemonium of cheers, shouts, and shrieks, and groans, lighted by the flames from cannon and muskets – blotched by fragments of men thrown high into trees by bursting shells. To lose the guns was to lose the battle. To capture them was to win it. In every great battle of the war there was a hell-spot. At Port Republic it was on the mountainside.”

General Taylor and the feisty soldiers of his three Louisiana regiments finally dislodged the Union defenders. Men as well as dozens of horses attached to the Union batteries were strewn across the bloody hillside. The victory was brief as the Union soldiers along Lewiston Lane reformed and charged at the unorganized Confederates. The Coaling changed hands two more times in bloody charges that were followed by fierce bouts of man-to-man fighting. The third and final Confederate charge captured the hillside as well as five of the six Union cannon. Turning the Union guns against the remaining Union soldiers forced General Erastus Tyler to retreat further down the river towards Conrad’s Store.

General Taylor and the feisty soldiers of his three Louisiana regiments finally dislodged the Union defenders. Men as well as dozens of horses attached to the Union batteries were strewn across the bloody hillside. The victory was brief as the Union soldiers along Lewiston Lane reformed and charged at the unorganized Confederates. The Coaling changed hands two more times in bloody charges that were followed by fierce bouts of man-to-man fighting. The third and final Confederate charge captured the hillside as well as five of the six Union cannon. Turning the Union guns against the remaining Union soldiers forced General Erastus Tyler to retreat further down the river towards Conrad’s Store.

George Hulvey

George Hulvey

General Fremont pursued the Confederate rearguard as it retreated to Port Republic, but just as the last Confederate troops arrived in the village, black smoke began to emerge as North River Bridge was engulfed in flame. Fremont and his men helplessly looked on from the left bank of the river as Jackson moved his force into the natural defenses of Brown’s Gap. A local boy named George Hulvey had been ordered to drag hay onto the bridge and set it ablaze. Hulvey was from the Cross Keys area and was serving in the 10th Virginia Regiment that was stationed in the village. He served with distinction and was later wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864 (the first battle between Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant). Hulvey’s wound resulted in the amputation of his left arm and he was subsequently discharged from the service. He later pursued a career in education and graduated from the University of Virginia in 1869. Mr. Hulvey taught for a few years before becoming a school principal, and in 1886, he was appointed as the Superintendent of Rockingham County Public Schools.

Jackson’s brilliant Valley Campaign concluded with back-to-back victories that reaffirmed Confederate control over the Shenandoah Valley. Over the course of 48 days, Jackson’s 17,000 men marched over 600 miles and defeated three Union armies totaling over 50,000 men. In addition to protecting the agricultural abundance of the Shenandoah Valley, Jackson’s campaign prevented Washington, D.C. from reinforcing McClellan on the Peninsula.

Jackson’s brilliant Valley Campaign concluded with back-to-back victories that reaffirmed Confederate control over the Shenandoah Valley. Over the course of 48 days, Jackson’s 17,000 men marched over 600 miles and defeated three Union armies totaling over 50,000 men. In addition to protecting the agricultural abundance of the Shenandoah Valley, Jackson’s campaign prevented Washington, D.C. from reinforcing McClellan on the Peninsula.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee

Confederate General Robert E. Lee

Just a few days before the Battles of Cross Keys and Port Republic, Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Confederate Army after General Joe Johnston was severely wounded at the battle of Seven Pines. Lee renamed his force the “Army of Northern Virginia,” and he engaged McClellan’s “Army of the Potomas” for a solid week of fighting at five different locations east of Richmond at Mechanicsville, Gaines’ Mill, Savage’s Station, Frayser’s Farm, and Malvern Hill (collectively known as the “Battles of the Seven Days”).

All of the Battles of the Seven Days were Union victories, but McClellan acted as though they were defeats. He responded by moving the “Army of the Potomac” down the Peninsula to the protection of Union gunboats at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. McClellan asked for reinforcements, but none were available because of Jackson’s successful campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. As Union ships slowly returned to Washington, D.C., a private in the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers gloomily scribbled in his diary, “Today we took a steamer and went up the Potomac past Washington and landed at Georgetown…It is hard to have reached the point where we started from last March, and Richmond is still the Rebel Capital.”

All of the Battles of the Seven Days were Union victories, but McClellan acted as though they were defeats. He responded by moving the “Army of the Potomac” down the Peninsula to the protection of Union gunboats at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. McClellan asked for reinforcements, but none were available because of Jackson’s successful campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. As Union ships slowly returned to Washington, D.C., a private in the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers gloomily scribbled in his diary, “Today we took a steamer and went up the Potomac past Washington and landed at Georgetown…It is hard to have reached the point where we started from last March, and Richmond is still the Rebel Capital.”

With appreciation of the wider conflict, a Virginian at the time wrote that Cross Keys and Port Republic were “those peculiar contests which act upon events around them, as the keystone acts upon the arch. With Jackson beaten here, Richmond, humanly speaking, was lost, and with it Virginia. With Jackson victorious, Richmond and Virginia were saved.”

SOURCES:

Fisher, Lewis F. No Cause of Offence: A Virginia Family of Union Loyalists Confronts the Civil War. San Antonio, Texas: Maverick Publishing, 2012.

Krick, Robert K. Conquering the Valley: Stonewall Jackson at Port Republic. New York, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1996.

May, George Elliott. Port Republic: The History of a Shenandoah Valley River Town. Staunton, Virginia: Lot’s Wife Publishing, 2002.

Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend. New York, New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1997.

Wayland, John. A History of Rockingham County, Virginia. Dayton, Virginia: Ruebush-Elkins Company, 1912.

Fisher, Lewis F. No Cause of Offence: A Virginia Family of Union Loyalists Confronts the Civil War. San Antonio, Texas: Maverick Publishing, 2012.

Krick, Robert K. Conquering the Valley: Stonewall Jackson at Port Republic. New York, New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1996.

May, George Elliott. Port Republic: The History of a Shenandoah Valley River Town. Staunton, Virginia: Lot’s Wife Publishing, 2002.

Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend. New York, New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1997.

Wayland, John. A History of Rockingham County, Virginia. Dayton, Virginia: Ruebush-Elkins Company, 1912.